Solar Panels That Are Better for the Environment?

Investigating the market use for CZTS, an emerging solar technology

Last updated 12-10-2023

Silicon solar is amazing

The eco-credentials of silicon as a photovoltaic material (PV) is well-established. Silicon solar panels typically repay their embedded carbon (the total carbon footprint from extraction to disposal) within 2-3 years, meaning that for most of their 25+ year lifespan, they are producing truly clean energy. Along with dramatic cost increases, this has allowed silicon PV to gain immense traction as a renewable energy source over the past two decades. Silicon now dominates the PV landscape with well over 90% of the market share. Notable non-silicon technologies are cadmium telluride (5% market share), CIGS (2% market share) and gallium arsenide (GaAs) based cells used in space (not mass-produced as they are very expensive).

But we still need innovation

Despite the incredible rise and success of silicon PV, new innovations will still be critial to reduce the impact of climate change. The IEA Net Zero by 2050 report anticipates that over 45% of the annual CO2 emissions savings by 2050 will need to be delivered by technologies still in development.

One notable issue is that recycling or re-use of silicon PV is not currently economically viable. There are large sums of money being offered by governments to anyone who can help solve the challenge posed by the rapidly increasing volume of PV waste we generate. It should be noted that PV waste is currently and will continue to be dwarfed by other forms of waste, but that doesn’t mean it’s not important to minimise it.

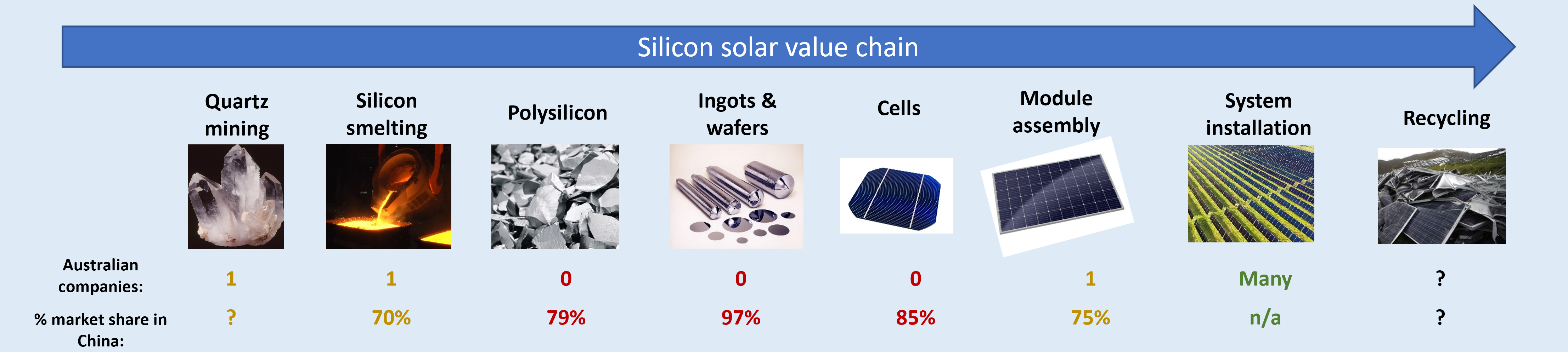

Another potential issue is that the vast majority of the silicon PV supply chain is shown above: it is concentrated in a single country. This could be seen through a geopolitical lens as a future energy security risk, and complicates creating a circular economy.

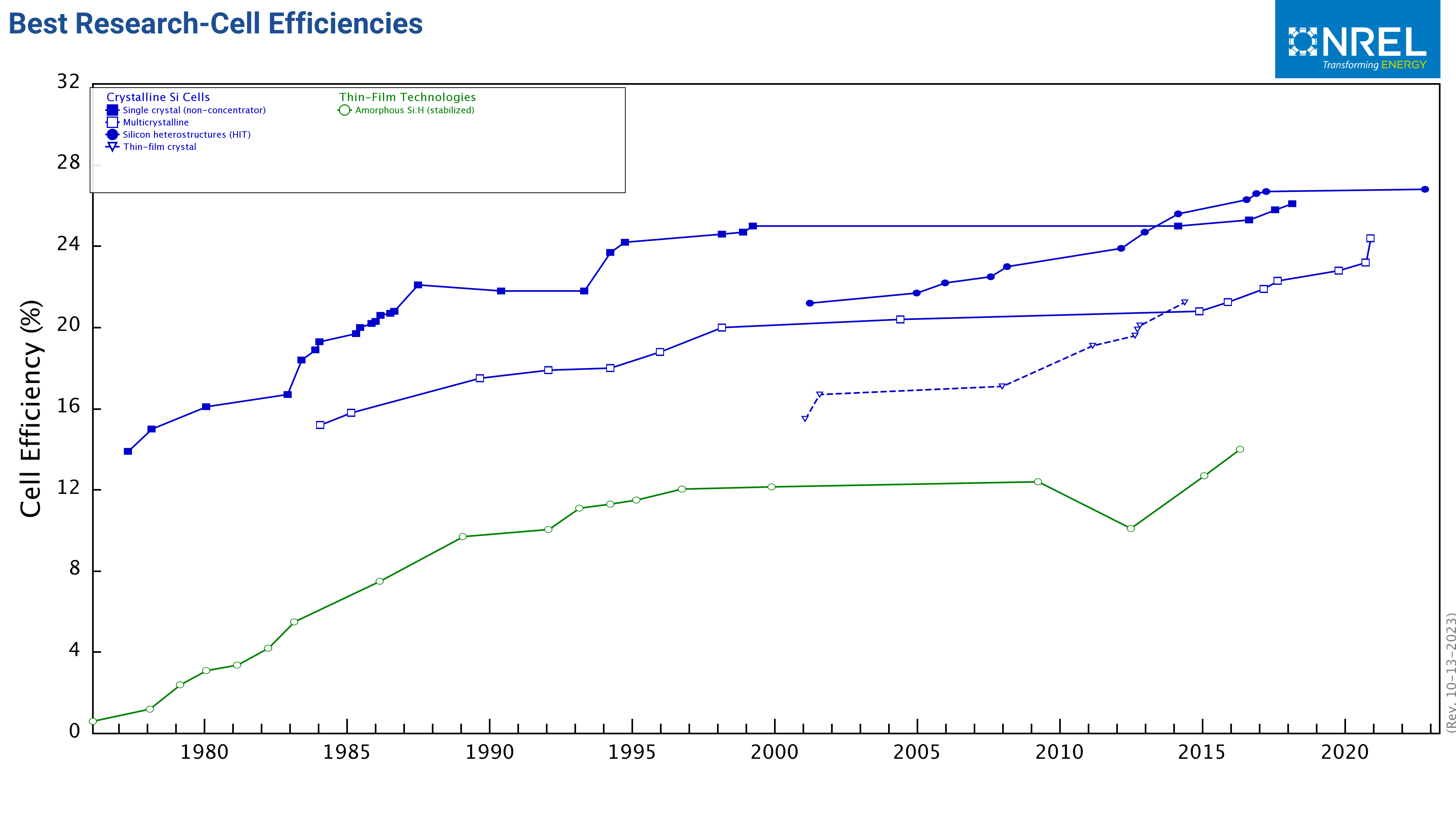

Finally, the rise in efficiency of silicon solar panels has stagnated in the past decade, and is so close to the theoretical limit (for silicon) that it will probably not increase signficantly from now. New PV technologies which can improve the efficiency of silicon without increasing the cost of energy produced would be highly desirable

These challenges underscore the pressing need for revolutionary solar technologies that are not only more efficent, affordable and simpler to manufacture but also easier to recycle compared to the current silicon solar panels.

Lightweight, non-toxic CZTS solar

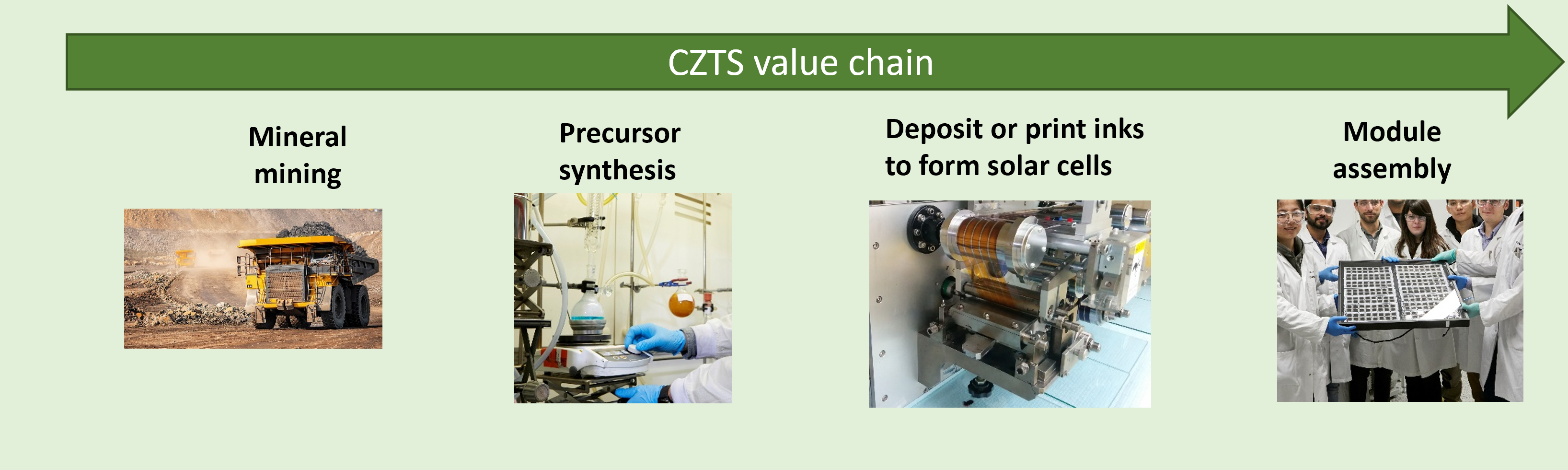

Researchers in the centre I work at are pioneering a new method to fabricate lightweight CZTS solar cells using only low-energy processes. (CZTS stands for ‘Copper, Zinc, Tin, Sulfur and Selenium’, which are the elements these solar cells are composed of).

This approach not only eliminates the use of toxic materials in many other emerging solar technologies (such as lead-rich perovskites) but also reduces embedded carbon when compared to traditional silicon solar panels, and in the long run, should be more cost-effective to manufacture and have even lower embedded carbon than silicon PV panels. The simpler manufacturing process allow for lower capital costs for a given production scale, which might afford local Australian manufacturing of CZTS PV that would provide both energy securty and local clean energy jobs.

PV modules made using CZTS are expected to be much lighter than conventional silicon PV, and potentially flexible as well, which could unlock PV uses in areas where silicon PV currently cannot work due to weight or flexibility constraints.

In 2023 I led a team tasked with critically evaluating and testing these purported benefits of CZTS PV to decide if, and how, CZTS solar cells could be brought onto the market and compete with existing silicon PV. This project was undertaken as part of CSIRO’s ‘On Prime’ program.

What we discovered

Our journey involved interviewing a diverse group, from the world’s leading silicon PV manufacturer in China to local architects, PV installers, and grid-scale solar farm managers. The goal of these interviews was to get a comprehensive understanding of the significant technical problems across the photovoltaics value chain and discern if solution-processed copper zinc tin sulfide selenium solar cells might be the answer.

Our research shed light on a few critical points:

-

Lightweight, flexible, and economically produced PV sounds great, but it will be challenging to compete with silicon directly in conventional rooftop or grid-scale solar farm installations. We heard from multiple sources that the extensive investment in silicon-specific materials, processes, and skills at every stage of the conventional PV value chain would be a huge barrier to allowing a disruptive new technology to enter the market. The industry’s risk-averse attitude, mainly due to the necessity for product lifespans exceeding 20 years, is another stumbling block.

-

CZTS could find its niche in areas where the panel’s aesthetics, flexibility, or weight overshadow efficiency concerns. Prime examples include building-integrated photovoltaics, warehouse rooftops (which often can’t bear the weight of heavy silicon panels), vehicle-integrated solar solutions, and IoT devices with embedded solar panels.

-

Assessing the recyclablability or end-of-life implications of a solar panel is not trivial. It often depends on how easily the various layers can be separated from each other which requires a lot of research and testing. Researchers and funders should consider this when deciding whether to scale up and commercialise a technology.

-

We met skepticism that Australian manufacturing of any PV product could be done at a scale that was competetive with silicon PV produced in China. If a new PV product was to be made in Australia, either an unfeasibly large initial investment would be required (on the order of $billions). However, if an initial niche market where CZTS holds a competetive edge can be identified, there might be some hope, especially if coupled to a means to rapidly expand via existing infrastructure for manufacturing (rather than building each plant from scratch).

-

Solar manufacturers and solar farm operators have an interest in enhancing the efficiencies of silicon PV through a tandem structure. This approach involves adding a solution-processed cell on top of a conventional silicon cell, increasing power output without the need for additional space. While there’s excitement around silicon/perovskite tandems due to their impressive results, CZTS cells, we believe, will provide longer product lifetimes and alleviate the toxicity concerns inherent with perovskites.

The power of tandems

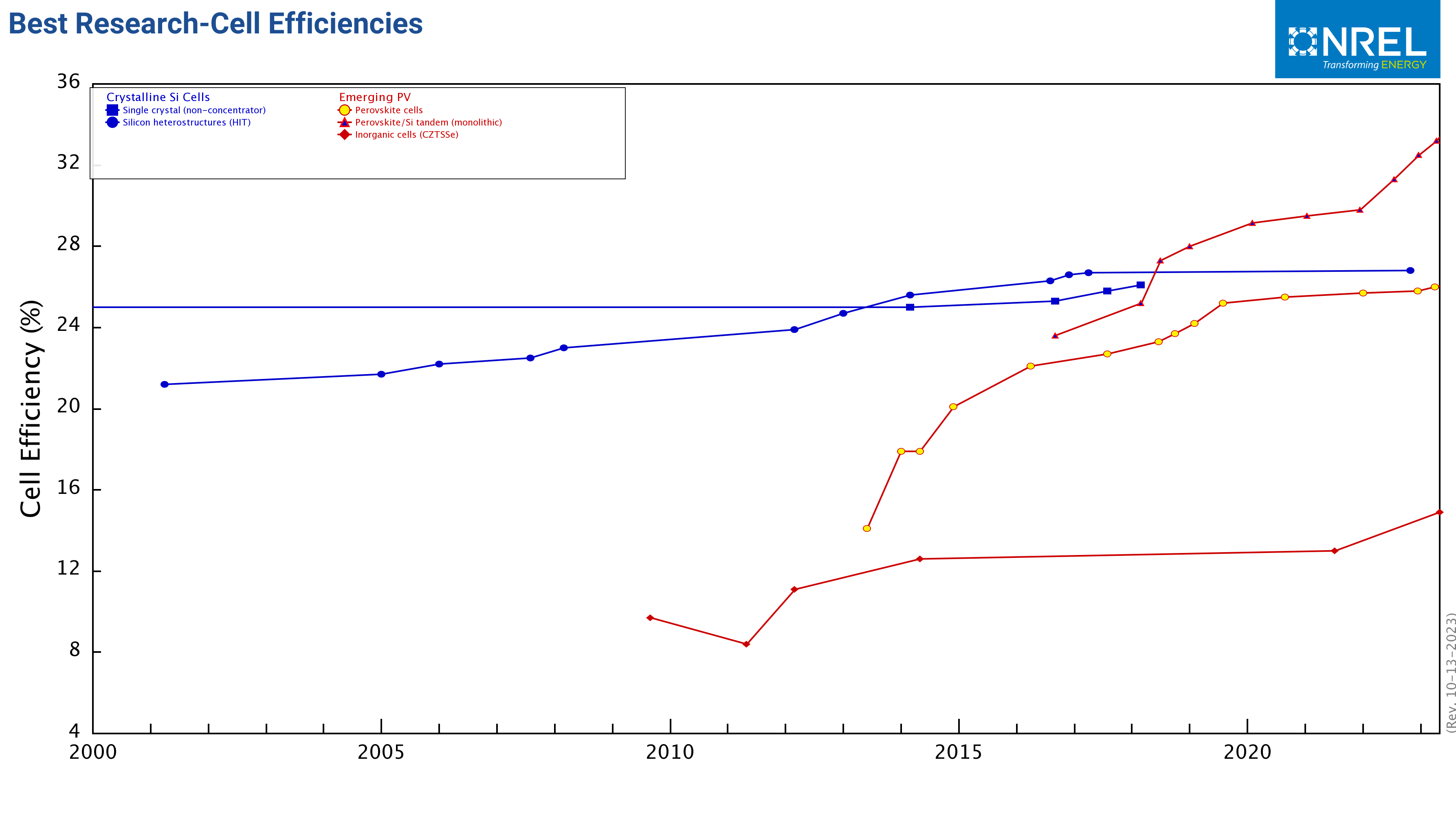

We concluded that a silicon/CZTS tandem PV product is the most likely means to get CZTS technology onto the market. The potential of this approach can be seen from the story of perovskite PV, shown in the graph below. I’ve removed most of the less common silicon PV technologies for clarity, and added in CZTS (red line at bottom), and perovskites, another emerging technology (red line with yellow circles), as well as a perovskite/Silicon tandem (red line, blue triangles):

Crucially, a tandem of perovksites and silicon (red line with blue triangles) is more efficient than just Si or perovskite alone, but due to the low cost of adding a perovskite layer onto silicon PV, it doesn’t cost too much more than just a silicon solar cell to make. Whether the cost of energy ($/W or LCOE) for a perovskite/silicon tandem can be lower than conventional silicon PV remains to be seen, but this is the hypothesis of one well-funded Oxford spin-out.

You probably noticed that CZTS efficiencies are lower on that graph than perovskites. That’s true, and it’s a hurdle that needs to be overcome, but there are two issues with perovskites that are holding them back:

-

Stability. Perovskites are famously unstable especially in contact with air and water. This is a problem for a tandem, because you don’t want to throw out a perfectly good silicon PV cell after 10 years because the perovskite layer is dead.

-

Lead. Perovskites are full of water soluble lead. There is a risk this could get into the environment either via damage to the cell, or end of life dumping into landfill.

CZTS solves both of these limitations: It is very stable and contains no lead. The major scientific hurdle is that the efficiency of CZTS is too low right now to be a proper contender for a CZTS/silicon tandem.

But that will almost certainly be solved - at which point, engineers and funding agencies are likely to be motivated to develop a CZTS/silicon tandem that can extract more energy than silicon alone, without creating concerns about stability or toxicity.

You can read another article on our findings, which received a $4,000 bonus to go towards our research, here.