FRED - a retrofit device to reduce research lab energy use

(with some analysis and thoughts on lab energy consumption)

Last updated: October 2023

Introduction

In the critical pursuit of energy efficiency, I’ve engineered FRED (Fumehood Reduction in Energy Device): a straightforward retrofit device designed to reduce the energy consumption in our research labs.

This innovative tool, constructed using cost-effective electronics and a few lines of code, has promising implications for the future of sustainable labs.

What is FRED

What: FRED is the Fumehood Reduction in Energy Device.

Function: FRED alerts researchers when they leave their fume hoods (vented cabinets for handling chemicals) open.

Performance: In a two-month trial, fume hoods utilized about 33% less energy post-FRED installation, translating to an estimated 3.3 tCO2e saved per hood. This implies a potential 3% energy reduction at a building scale.

Open Source: FRED is open source. Instructions for creating your own FRED are available here.

Notably, an analogous device and a start-up company have been developed by MIT researchers, which further corroborates the effectiveness and viability of such a device.

The Imperative to Reduce Energy Demand

Transitioning to zero-emissions energy as fast as possible is only half the battle to mitigate climate change. It is equally important to drastically reduce our energy demand. The International Energy Agency (IEA) has estimated that, even with widespread renewables uptake, we need to triple the current rate of energy efficiency improvements in buildings over the next ten years.

Research Labs in Focus

Research labs should not be exempt from this. But how much energy do research labs use? I had a look at the research building I work in at the University of Melbourne (Chemistry).

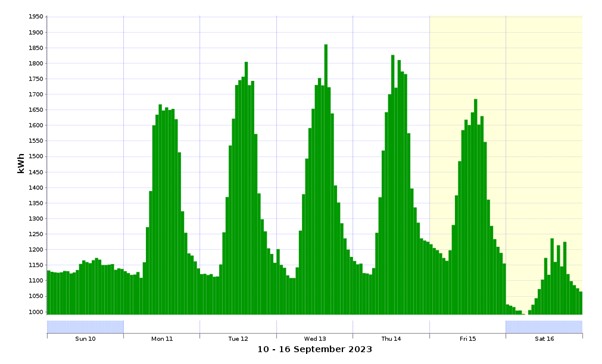

Over a single week, there was a fairly constant baseline of around 1,100 kWh energy consumption per hour. During working hours, consumption peaks between 1,500-1,900 kWh per hour. To contextualise these numbers, the fridge/freezer in a residential house might use 0.25 kWh per hour. Over the past year, energy consumption was around 27-28 MWh per day on the weekend and around 30-40 MWh per day Mon-Fri. In total, from September 2022 to September 2023 our building consumed 11,575 MWh of energy.

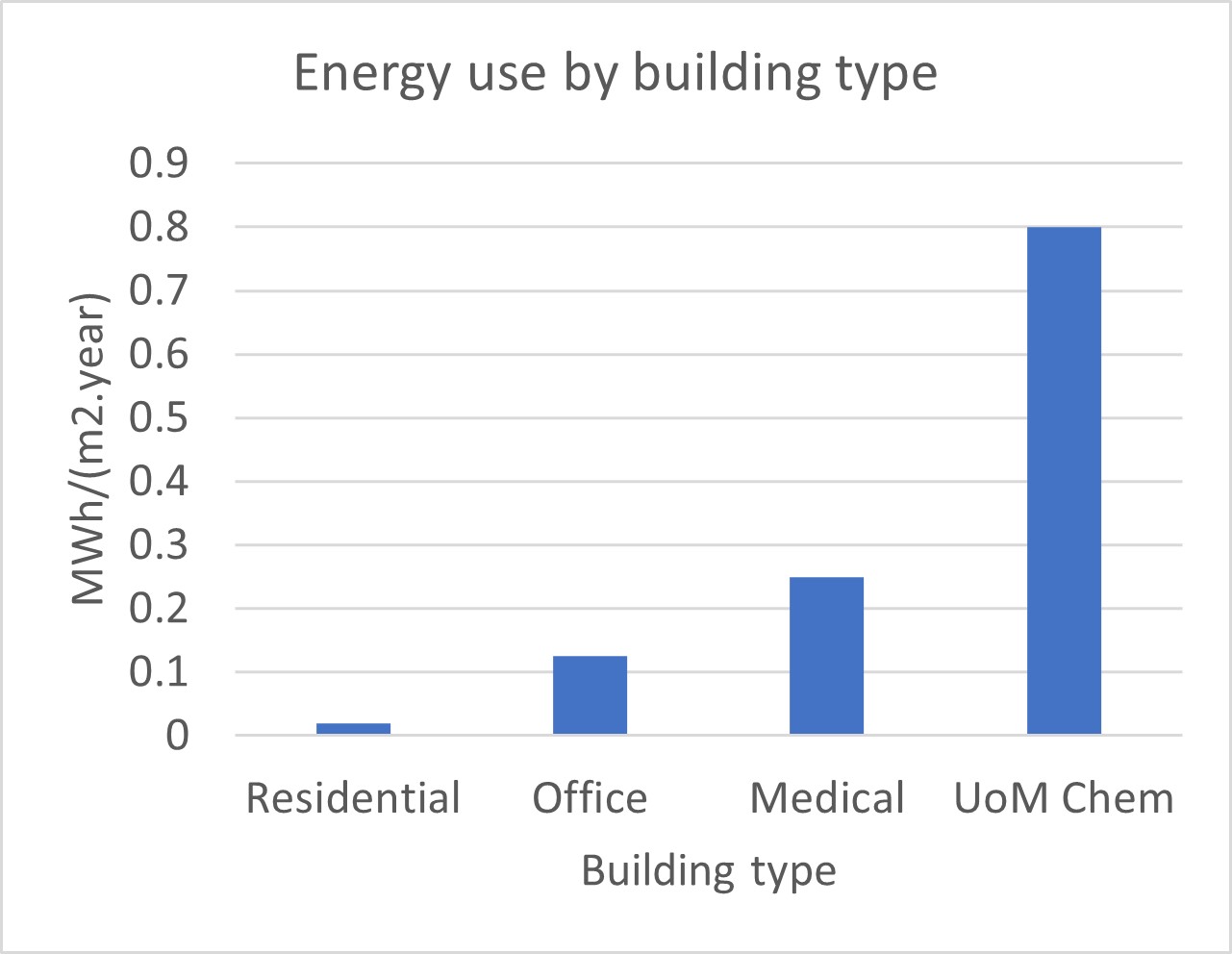

These numbers are hard to understand without a comparison to other industries or residential energy use. To do this, I’ll take average/typical numbers for energy use (per year) for each sector and divide by floor area. (Why floor area? This is how the data is presented in the DCCEW “Commercial Buildings Energy Consumption Baseline Study 2022” which makes it a convenient way to compare energy consumption). For residential, I took the average home energy use in Victoria from the AER Residential Energy consumption benchmarks (Table 9, averaged across all DNSPs) and the average floor area of a new house in Victoria in 2020-2021 from the ABS.

By this measure, our building is using about 40x the energy as a residential space and 3.2x a medical space (per unit floor area). This isn’t surprising, as research buildings have lots of equipment (lasers, spectrometers, liquid nitrogen tanks, air extraction/flow fans, etc) and we have hundreds of students (undergraduate and graduate) doing research or coursework experiments during the day.

Targeting Major Energy Wasters: Fume Hoods

With this in mind, I set about to see if we could make research labs in our building more efficient without having to rebuild them or buy any expensive new equipment.

While common practices like turning off lights and equipment are already in place, it turns out there are bigger energy wasters. My prime candidate for energy reduction was the ‘fume hood’ — a leading cause of energy wastage.

A fume hood is a big cupboard with a clear plastic, vertically sliding door called a ‘sash’. Researchers working with hazardous chemicals do so in a fume hood, and powerful fans at the top of the fume hoods extract dangerous chemical vapours. If left open, each fume hood can devour 2-3 kWh every hour, about the same as 3 residential houses. To make matters worse, our building contains around 100 fume hoods, most of them without any features to automatically close or turn off if they are left open.

The challenge? Encouraging researchers to shut them when not in use.

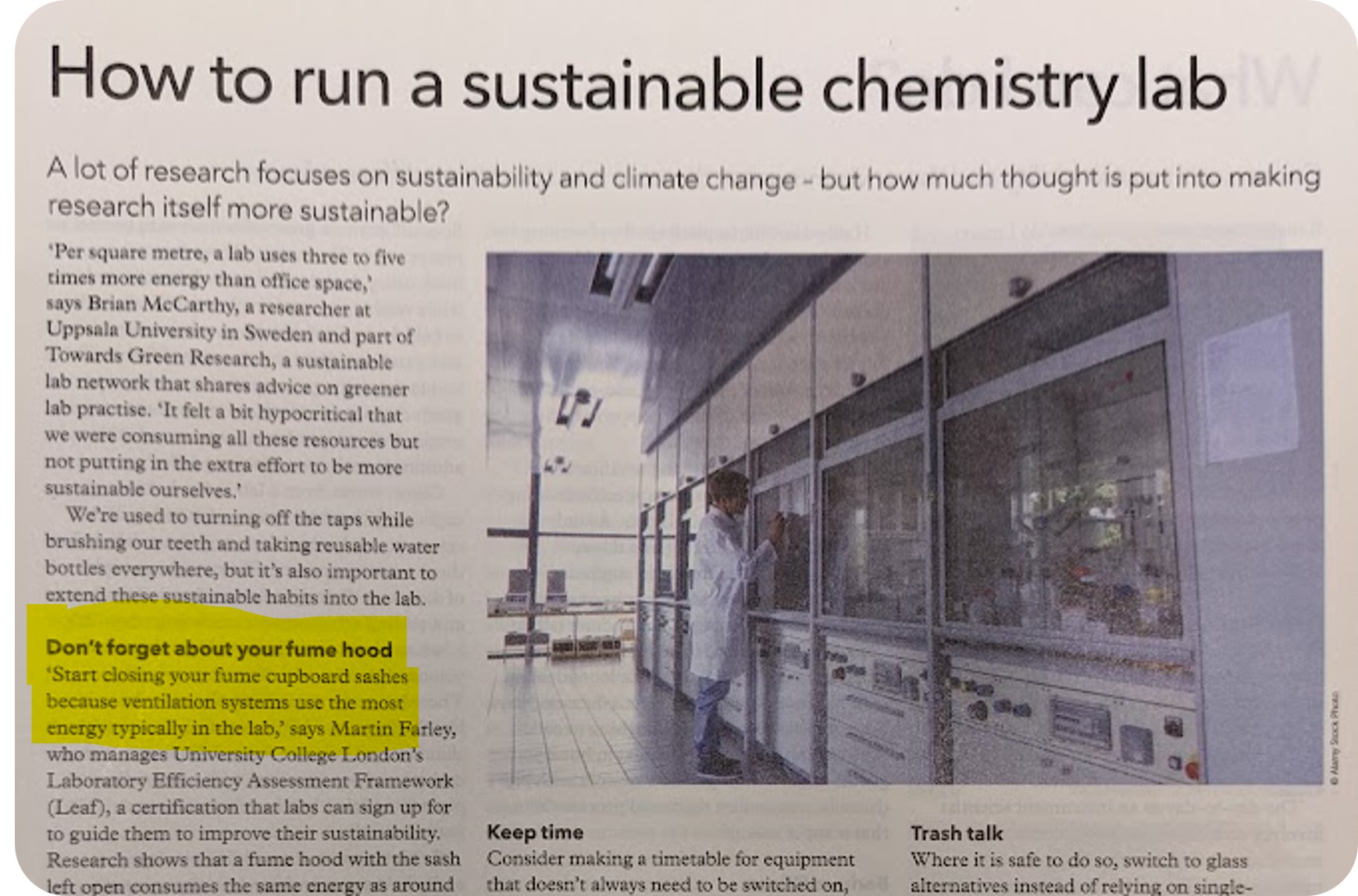

The “Chemistry World” article “How to run a sustainable chemistry lab” (December 2021) also identifies hoods as a major culprit of energy waste in labs and various LinkedIn posts and even peer-reviewed publications confirm that fume hoods are a big source of avoidable emissions from labs.

A FRED is Born

I’d been learning Python and playing around with Raspberry Pi microcontrollers, so I decided to build a retrofit device which would detect fumehoods being left open and encourage people to close them.

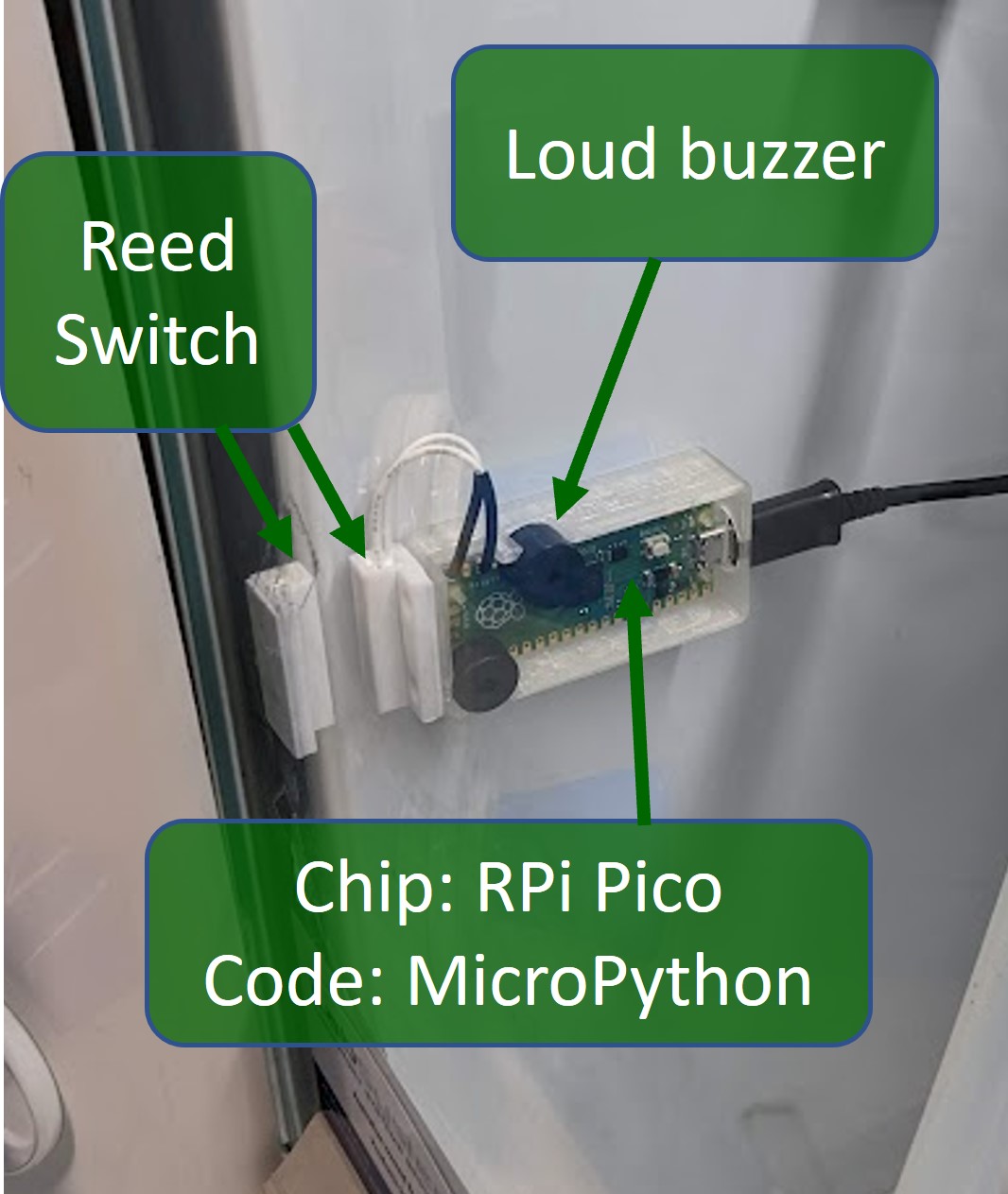

The result was FRED (Fumehood Reduction in Energy Device). FRED is a cheap fumehood retrofit using a Raspberry Pi Pico (under AUD$10 at the time of writing) and a few off-the-shelf electronic items (two buzzers and a magnetic switch). The whole thing costs just $20-25 per fumehood. I also designed a little 3D printable case that helps to enclose it all and line up the sensors.

Once assembled, which requires only a few minutes, FRED is attached to a fume hood. A sensor tells the Pi if the fume hood is open or closed.

If the fume hood is left open for more than 1 hour, FRED starts to make a loud, annoying buzzing noise.

With a little more work, an advanced version of FRED I made also posts facts about energy consumption and climate change onto our lab’s Teams channel.

Last but not least, FRED plays a very happy and satisfying little riff as a reward for closing a fume hood is closed. (The carrot approach).

The results? A significant decrease in open fume hoods.

Measuring FRED’s Impact

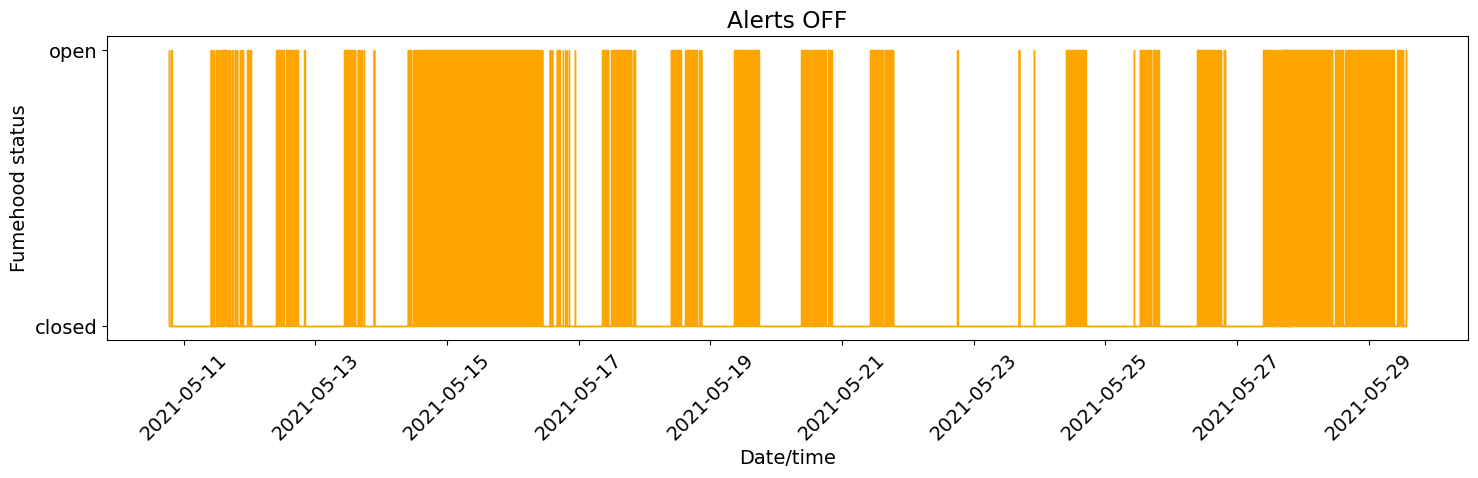

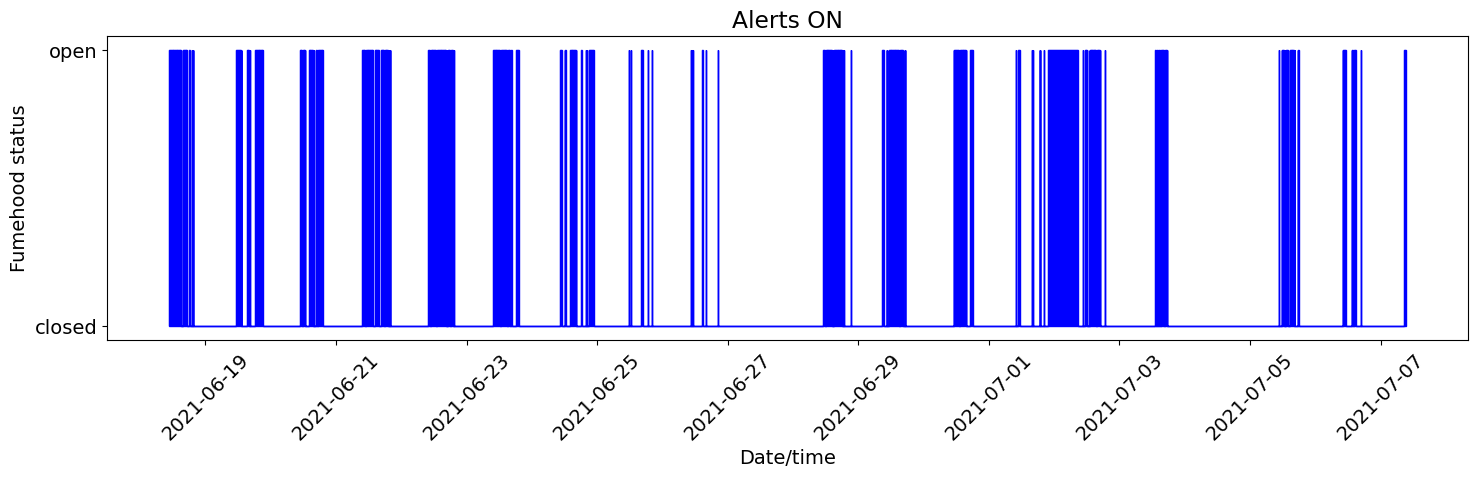

FRED is easily capable of data logging so I ran a long-term experiment to see if FRED had a meaningful effect. I left FRED with the buzzing noises (and Teams posts) off in a fume hood for 1 month to log baseline data, then turned on FRED’s buzzers and posting and recorded for another month the effect on how often and how long the fumehood was left open.

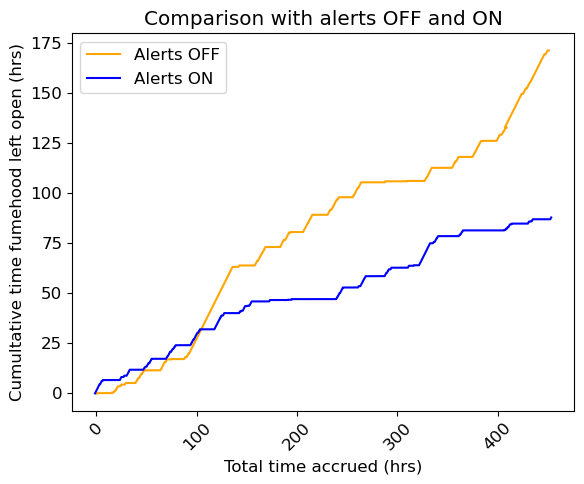

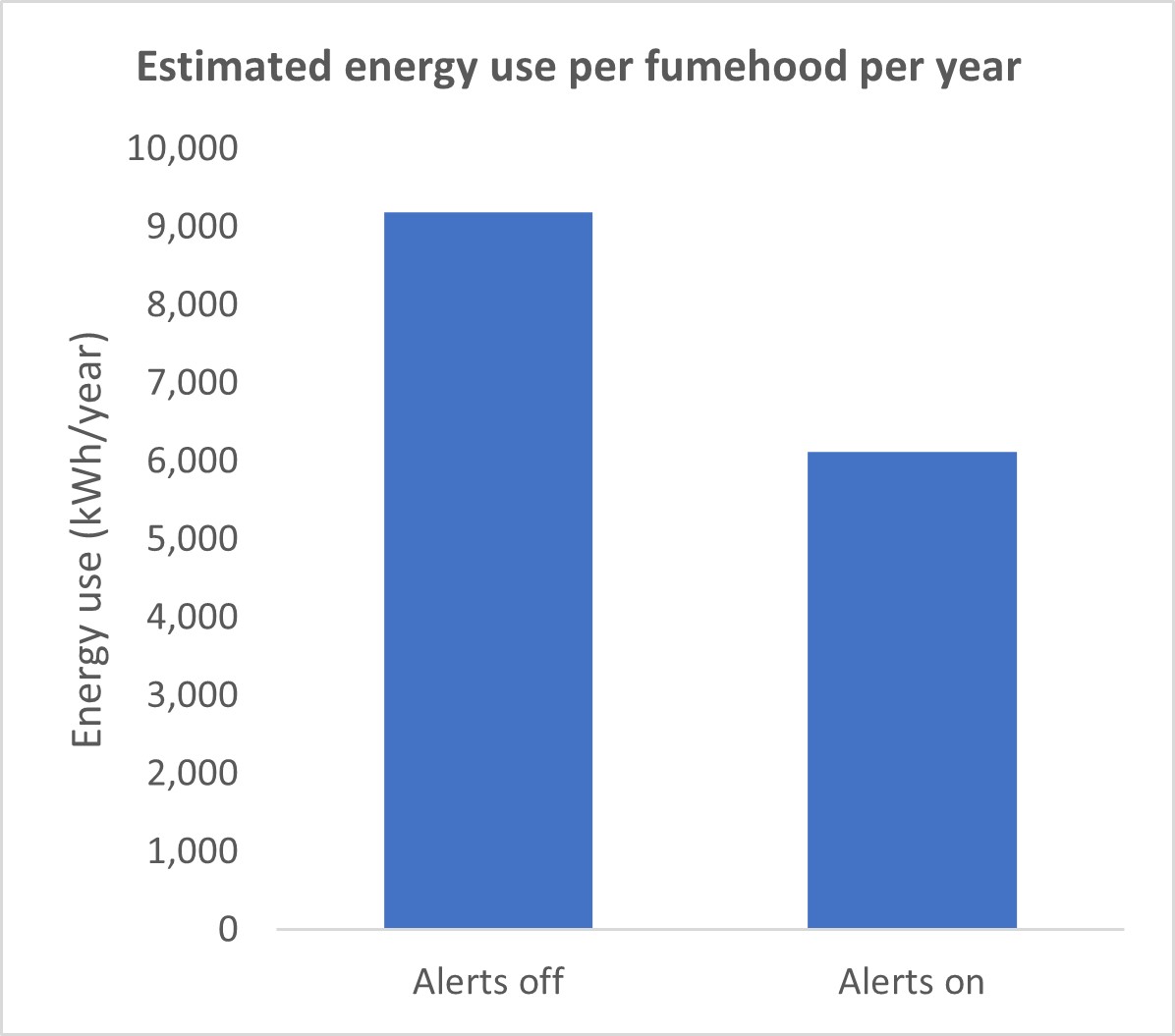

The data shows FRED leads to a clear reduction in time the fumehood is left open, driven mostly by significantly fewer episodes where a fume hood is left open for over an hour. Using the LBL fumehood energy use calculator available online with inputs based on our fume hoods, I converted time left open into an estimated energy consumption.

This is a back-of-the-envelope way to calculate energy use, but the result was clear: A significant reduction in energy consumption of around 33% or around 3 MWh per year per fume hood. When installed in all four fumehoods in our lab, this equates to about 13 tCO2e avoided (using the DELWP GHG coefficient of 1.09 tCO2e/MWh from 2021), roughly equivalent to removing 3 cars from the road. FRED also saves whoever pays the bills for our lab around $2,500 per year, assuming an energy price of $0.21/kWh.

Potential for Larger Impact

The data above is just for one lab – we estimated there are around 100 fume hoods in the Chemistry department alone. That means we could reduce the total energy consumption of our department by around 300 MWh per year, around 2-3% of the current 11,500 MWh yearly consumption figure, and over 300 tCO2e avoided (they yearly equivalent of approximately 70 cars).

That’s pretty decent for a retrofit that costs $25 and only takes a few minutes to install.

Other Approaches

As a final bit of due diligence: surely there’s existing ways to solve this obviously quite significant energy use problem? The answer is yes, but at a significant cost. I asked our lab system provider to quote a retrofit or refit of our furmehoods to incorporate an energy saving feature that closes the sash (or at least alarms when left open) and we got a quote of just over $4,000 per fume hood (excl GST) which is about 150-200 times more expensive than FRED.

As a final note, I’ve recently noticed a similar device described by a team at MIT and an assosciated start-up company. They arrive at encouragingly similar results to those obtained by FRED.

Where is FRED?

To propagate FRED’s benefits, I’ve open-sourced the code, 3D printable case, and installation guide, making it freely available on GitHub here.

Acknowledgements

The FRED project was greatly assisted by the discussions, advice and superior soldering skills of Jack Heywood-Day and Trent Ralph. Thankyou!